Author: Tom Mullen

The year 2009 struck a nadir point for the cork industry. Sales of wine corks had been declining since 2000, replaced by alternative closures that included aluminum screw caps, plastics and glass. The fall of cork had been predicted multiple times in the past. In 1993, The New York Timeswine writer Frank J. Prial predicted ‘1993 may see the beginning of the end of the wine bottle cork.’ In 2002, Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon Vineyard in California and British wine writer Jancis Robinson attended a ‘Funeral for the Cork’ service in New York City—where, over a cork constructed mannequin at a mock wake, they gave eulogies to the death of natural cork enclosures. In 2004, renowned wine critic Robert M. Parker Jr. predicted that by 2015 cork would be used to seal only a minority of wine bottles, and that screw caps would become the new industry standard.

By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, such prophecies rang prescient. The world of wine closures was shifting dramatically, and cork sales were on the decline. Not only wine closures, but the entire cork industry was threatened because bottle stoppers represent 70% of all production.

Times have changed.

‘We are in completely different territory now than anyone thought possible then,’ said Carlos de Jesus, Marketing and Communication Director for Amorim & Irmãos, the largest cork producer in Portugal and the world. ‘2008 was the toughest year ever.’

Sales of wine corks are rising again. According to the Portuguese Cork Association (APCOR), cork exports grew 30% between 2009 and 2016, representing an annual growth of 4%. (Of seven Mediterranean countries producing cork, Portugal has a third of all cork forests, while Spain has a quarter; Portugal exports two thirds of processed cork products, while Spain exports 17%.)

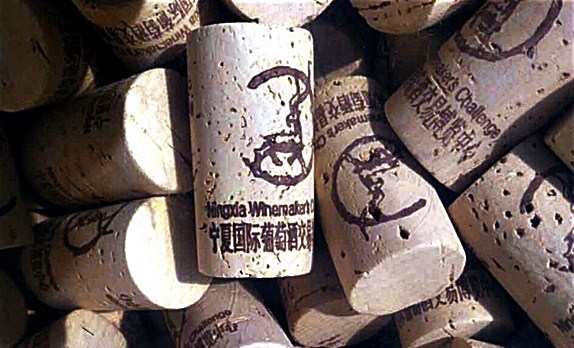

Reasons for this shift to an increase in sales during the past decade include an aggressive, focused effort to reduce cork contamination, as well as a robust interest in the use of cork within Asian markets.

The nosedive in cork’s popularity centered on a problem of contamination.

Wine that is contaminated by a compound known as 2,4,6-trichloroanisole, or TCA, can smell like moldy cardboard. Though not harmful to health, it can cause drinkers to wince before inverting their open bottle over the nearest drain. TCA is easier to detect in wines with alcohol levels of 10% than those with higher levels such as 14%—giving it a higher incidence of being detected in, say, Champagne or Riesling.

Born in the presence of phenols, chlorine and mold, TCA can enter a winery through various contaminated avenues—including old crates, humidifiers, or drains where a chlorine product was recently dumped. It can also enter wine through contaminated corks.

TCA is potent enough that humans can detect it through smell when the concentration is only five nanograms per liter. This is the same as saying five parts per trillion (if you live in the USA, UK, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil and Soviet Union, much of Africa and a few Caribbean isles, where a ‘trillion’ is the number 1 followed by 12 zeroes. Otherwise, a ‘trillion’ means the number 1 followed by 18 zeroes. For this article, we’ll use the first convention: 12 zeroes).

This humanly detectable concentration of about five parts per trillion is miniscule. It’s like counting one second of time within 6,340 years.

In the mid 1980’s, worldwide reports increased of wines tainted by TCA (which is often called ‘corked’ wine, a misnomer because other sources of contamination exist). This occurred for a variety of reasons. These include revolution, tradition and interior decor.

In 1974, a leftist uprising in Portugal resulted in various owners and workers being ejected from their own cork plantations and replaced by inexperienced revolutionaries eager to try their own hand at agriculture, often with poor results. Because cork is debarked from any one tree only every nine years, the impact of their short-term but slipshod harvesting and mismanaged production still reverberated in the world of cork a decade later.

Tradition also delayed recognition of the TCA problem.

As George M. Taber wrote in his book To Cork or Not To Cork, ‘…cork’s long monopoly was also bad for cork producers. Fat and sassy, they became complacent. Innovation was virtually unknown, and prices only went up.’

Although a study was produced in Switzerland in 1981 by Hans Tanner identifying TCA as an occasional contaminant of corks, producers (many being in Portugal) took virtually no action. Why should they? Cork producers had enjoyed an uncontested monopoly on wine enclosures for centuries. Few were aware of this study. Most producers were small operations, run by families more likely to enjoy glasses of Arinto wine while watching soccer on the television during evenings than to peruse any Swiss technical journals written in German.

Meanwhile, opportunities blossomed for producers of alternate closures. Such bottle closures were not new. The first screw cap patent was filed in the 19th century, and E.&J. Gallo wines of California had used non-cork closures between the end of prohibition, in 1933, and the 1980’s.

These alternative closures were touted as beneficially brushing away problems of TCA taint, reducing production costs and making it easier to open bottles. Yet such enclosures include their own problems. Synthetic—plastic—stoppers allow more air to enter a bottle than cork (and can be challenging, once removed, to reinsert into a bottle neck), while screw caps so effectively block out oxygen that some wines become what is known chemically as ‘reduced,’ with can produce its own disagreeable taste.

Aware of the impacts of TCA problems and growing competition, the cork industry invested more than $850 millon (700 million Euros) over a 15 year period to improve performance. A few cork producers also dramatically shifted strategies. They realized that eliminating TCA from cork involves both field and factory modifications (such as not using cork bark which grows close to the ground; storing it off the earth and boiling it to remove contaminants within stainless steel vats). Multiple wineries in the 1990’s ejected contaminated equipment such as barrels painted with wood preservative, as well as porous plastics.

The process also involves detection.

The tool for detecting TCA is gas chromatography—mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Basically, you put a cork in a little box that sucks out gasses, measures their individual volatilities, and then compares the ‘signatures’ of these components to identify each. This expensive technology was a necessary ticket for producers to identify batches of contaminated cork. It also represented a potential means for their industry to escape obsolescence.

Amorim witnessed a dramatic loss of cork sales between 2000 and 2009. As one countermeasure, they invested in costly GC-MS technology, realizing it would take time to scale up operations. Today the company’s patented NDtech system utilizes some 60 GC-MS units to analyze individual corks and identify TCA levels above one half part per trillion. Whereas in the 1980’s a lab technician could analyze perhaps six corks a day using this technology, today each new machine can analyze one cork each 16 seconds. That figure is projected to drop to 10 seconds within months as the robotic components that insert and remove corks are further streamlined.

Not all cork closures are cylinders punched directly from bark, or ‘natural corks.’ A hefty slice of production is also dedicated to less expensive ‘technical’ corks. Fabricating these involves shredding cork, treating the granules using pressurized water and steam, then reconstituting the granules—with heat and a food-grade binder—into a stopper. These are often capped at both ends with discs made from natural, punched cork (or capped twice at one end, as in the case of Champagne stoppers). Few wine drinkers even notice the difference between technical and natural corks.

With technical corks, rather than using GC-MS technology to inspect for TCA, the granules are rid of contaminants via humidity treatment, while the end disks are individually inspected (and rejected, as required) after being imaged and X-rayed in separate machines. The process recycles unused cork segments, so reduces waste. Originally developed in Portugal in the 1980’s, this technology has dramatically evolved during the past decades.

‘We believe that we need to have different types of stoppers for different types of wine. The Two Buck Chuck does not necessarily have to take the same cork as the Screaming Eagle,’ said António Rios de Amorim, CEO and President of Amorim.

On factory floors in cork production towns such as Santa Maria de Lamas, machines punch and chamfer and polish and sort and brand corks; devices measure torque and extraction forces required to pull champagne corks from bottles; caged robots manipulate strips of cork, and computer algorithms—in the blink of an eye—compare faces of individual cork discs to a database of photographs in order to grade and sort each piece for quality. Within new laboratories, wheeling mechanical arms insert corks into chambers to parse their inner chemistry. The traditional universe of producing cork has been slapped by high gear technology.

Discussions about which wine closures may be ‘best’ can be as emotionally charged as talking politics or sports. Although rancor appears to have diminished over the past two decades, there are still hardcore devotees to screw caps, alternative stoppers and corks.

Europeans tend to stick with traditional cork closures (which are also produced on their continent), while winemakers on the opposite side of the globe—in New Zealand and Australia—have gravitated to screw caps. According to Wine Business Monthly 2017 Closure Survey Report—for small U.S. wineries (producing less than 50,000 cases per year) overall ratings for closures remained highest for natural cork for the past eight years, followed (in 2017) by aluminum screw caps and next by synthetic closures.

Often wineries use more than one closure. French winemaker Jérôme Eymas, from Château La Rose Bellevuein Bordeaux, uses different closures for different wines.

‘For reds we use natural corks, for our whites—technicals. For rosé we use screw caps because it’s easy to drink and will not be stored long. Even local customers say, ‘no problem.’ ‘

Wine producers in Australia and New Zealand are also weighing up advantages and disadvantages of different closures.

Stefano Lubiana Wines, located on the southern island of Tasmania, Australia, commented: ‘We used screw caps across the board. However, recently we’ve switched back to cork for all our premium reds. Partially, we feel the wines age differently under cork and it may be a little more forgiving to reductive characters in some of our wines. Partially because pulling a cork is more enjoyable than twisting a cap. And partially because we’ve greater confidence in corks these days with the introduction of screening of TCA by cork manufacturers. We still use screw caps on our whites and fruit driven reds, however, to preserve freshness. Obviously, the lower cost of screw caps is also a factor in choice.’

In New Zealand, where screw caps dominate as wine closures, Jo Mills of Rippon Vineyard in Central Otago told how all their wines are under technical (Diam) corks, while only one is under screw cap—their Osteiner. Originally the screw cap was placed for ease of opening during their summer concert series. However, they decided to keep the original bottle, label format and screw cap. ‘No scientific decision,’ wrote Mills. ‘Purely one based on aesthetics!’

Just as microwaves did not replace traditional ovens, e-books did not displace paperbacks and credit cards have not caused the death of cash, alternate closures have not displaced cork as bottle closures, but supplement them in a world where overall demand is increasing.

Cork is a bizarrely versatile and lightweight material (it is 90% air). It insulates against sound, vibration and temperature, which makes it attractive for flooring and aerospace industries, while its elasticity and semi-porousness makes it desirable for winemakers. Within one typical wine cork there are some 800 million individual cells, each being 14-sided (‘tetrakaidecahedrons’) and each composed of five layers of natural material that provide structure and strength. It is an attractive yet puzzling material: we are still uncertain how permeable it is to the flow of oxygen, which impacts the eventual taste of stored wine.

At the Portuguese cork producer M.A. Silva Cortiças, located in Mozelos, Marketing Manager Nuno Silva explained why he chose his work. ‘This is the world of cork,’ he said. ‘It is a beautiful world where the forest is the soul of our industry. I love it.’

Source: https://www.forbes.com/sites/tmullen/2018/02/05/why-wine-corks-are-on-the-upswing/#4120f0f56c5d